RINGDOCUS

A piece of amateur taxidermy from 1886, turned roadside attraction through most of the 1900’s, turned cryptid in 1999, then stolen from us by Montana in 2007.

Of course, Montana disagrees… At the heart of the disagreement here between our two great states, there is an interesting question of the point at which begins cryptozoological life:

The Montana story: Hero is the Montanan who shot the animal: Israel Ammon Hutchins…. The Ringdocus was shot in Montana, then stuffed in Idaho, then kept in Idaho, then not returned to its home until 2007.

The Idaho story: Hero is the Idahoan who taxidermized, named, and displayed the animal: Joseph Sherwood… A wolf was shot in Montana, then the Ringdocus was accidentally/on-purpose created in Idaho, then grew up in Idaho, then grew old in Idaho, then was stolen from us in 2007.

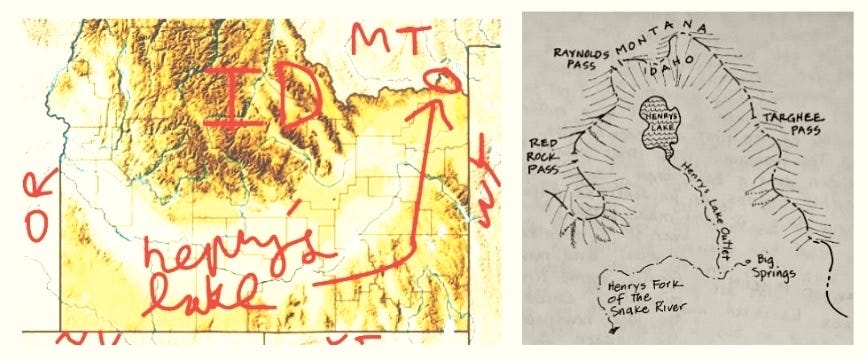

In this entry, I tell the Idaho story.1 It takes place at the northeasternmost jut of the Snake River Plain, just south/east/west of the continental divide, on the shores of a lake there called “Henry’s Lake”.

Or say, “....in the wilds of the upper midwestern United States…”.2 See Loren Coleman and Jerome Clark’s Cryptozoology A to Z: The Encyclopedia of Loch Monsters, Sasquatch, Chupacabras, and other Authentic Mysteries of Nature, published by Simon and Schuster, 1999:

Shunka Warak’in: In the wilds of the upper midwestern United States lives a frightening-looking, primitive wolflike beast known to Indians and early pioneers. The Ioway, as well as other tribes, even have a name for it: shunka warak’in (“carrying-off dogs”). Little has been written about this animal because records of it are relatively rare… Nonetheless, evidence does exist for this new addition to the cryptozoological menagerie.

1: Ringdocus to Shunka Warak’in:

The “evidence” they are talking about here is our stuffed mount of the Ringdocus... At the time (1999), it had been last seen at the Sherwood Store/Museum at Henry’s Lake, which had closed in late 1980’s, or earlier 1990’s.3 So, for their evidence of this evidence, Coleman and Clark relied on a one-page bit in a science-memoir written by a biologist (and grandson of Israel Hutchins) named Ross Hutchins. See page 50 of Ross Hutchins’ Trails to Nature’s Mysteries: The Life Workings of a Naturalist (1977):

Coleman and Clark quote the part between the red-brackets (with a few cuts) — reproduce the photo, but change the caption:

This is a mounted example of the Shunka Warak’in that was reportedly exhibited at various times in the west Yellowstone area and a museum near Henry Lake in Idaho. Its whereabouts today are unknown.

The entry then briefly mentions that this association (ringdocus = shunka warak’in) was first suggested to Loren by an Ioway man named Lance Foster. Ten years later (3/3/2009), Lance Foster (now a professor at the University of Montana-Helena College of Technology) will elaborate in his blog: paranormalmontana.blogspot.com — post title: “Shunka Warak’in: A Mystery in Plain Sight”. He will explain how, while working as an archaeologist at the Helena National Forest in the early 1990’s, he encountered a “little sketch of the animal” on the pages of a book written by a coworker. The coworker was Rae Ellen Moore, landscape architect. The book was Just West of Yellowstone: A Guide to Exploring and Camping: A Travel Sketchbook of the Area West of Yellowstone National Park (1987). I just ran to the library to look at their copy, and it is very nice:

Foster continues:

(...)

Apparently, it was from these cryptozoological contacts and resources that Loren Coleman got Ross Hutchins’ 1977 book — this which (see above) gives the now classic story of Israel Hutchins’ slaying of the unclassified beast of Henry’s Lake (just missing a few details: the human-like screams of the shunka warak’in, etc..) — and which also informs us that, at Henry’s Lake, Sherwood

…called it a “ringdocus”.

2: Guyasticutus to Ringdocus:

Heading back further now…. Ross Hutchins closes his 1977 account with this very-interesting Q and A:

Was it, as some have theorized, a hyena escaped from a circus? The nearest circus was hundreds of miles away. Ringdocus was just another mystery of the mountains, probably never to be solved.

Remember for later: “...some have theorized…escaped from a circus?”

Also note the sorta-implied definition: a “mystery of the mountains” = a mystery that is, more or less, inherently unsolvable. This is good. It is also good, though, to make some further distinctions. Like, why unsolvable? Say: Some mysteries of the mountains are unsolvable because they are too deep. You go to solve them in the mountains and you get lost in the mountains.... Others, meanwhile, have zero depth whatsoever. You go to solve them in the mountains and you bang your forehead against the 2D picture of their misty-ness in the distance — you get increasingly confused and lost-feeling as you continue to bang your forehead against the 2D picture of their misty-ness in the distance…. Say: The former sort of ‘mystery of the mountain’ is practically unsolvable (always deeper…). The latter sort, meanwhile, is actually unsolvable (“Deepest”...). It can be easy to confuse the two — important to remember the difference though because, arguably, the latter sort of mystery is really no mystery at all. This is what Wittgenstein says (TLP 4.00301):

The deepest mysteries are really no mystery.

He is talking about the grammatical confusions of a few ancient aristocrats (these which we now call “Problems of Philosophy”), but I think it often applies to more-realistic-seeming historical confusions, too. I think you should get suspicious whenever its language starts showing on the surface of the mystery. See again this name: “ringdocus”... Starting at Ross Hutchins’ 1977 account of the creature, trying to look further backward, this apparently-biological mystery of the mountains transforms immediately into an etymological mystery…

For starters, as far as I can tell, Sherwood did not call it a “ringdocus”. The name was unknown to Foster, and was not mentioned by Moore in 1987. The name was also not mentioned in the most complete pre-1977 account of the animal I can find — an article in the Salt Lake Tribune Magazine, 4/24/1948, titled “The Weird Wolf of Henry’s Lake”... By this point, Joseph Sherwood had been dead almost thirty years. What the Tribune describes as “Sherwood’s Natural Museum of the Unnatural” is run by his widow, Mary Anne. It had been a family home, stage-stop, gas station, post-office, grocery store, museum, etc.. It was built in 1899, 13 years after the killing/stuffing of the Ringdocus, just before Mary Anne married Joseph. The Tribune continues:

The Tribune then describes the contents of the museum:

Mostly though, the Tribune focuses on the “Weird Wolf”.

It says that what Sherwood named this creature was “Guyasticutus”. It even illustrates the moment of the creature’s christening with a little cartoon:

In the comments-section of Foster’s blog, great-grandsons of both Sherwood and Hutchins agree:

We all knew the animal as Guyasticutus…not the other names attached to it today.

And there’s no reason to doubt them, or the Tribune… As far as I can figure, the only sensical explanation for the coexistence of this name with the vaguely similar-sounding “Ringdocus” is that, through no fault of his own, Ross Hutchins was incorrect when he said that what Sherwood named the creature was “ringdocus”... How he might’ve got here from “Guyasticutus” is not hard to guess: probably some simple verbal mistransmission, or mental misremembering of some sort or other — maybe a combo of these things… Say Like: “Ringdocus” is the natural result of the series of verbal-to-memory/memory-to-verbal approximations/re-approximations that would’ve occured as this self-consciously ridiculous word (“Guyasticutus”) made its way from Sherwood’s mouth, sometime pre-1919/post-1886, to the other side of grandson Hutchins’ pen in 1977.

(...)

Before continuing, a super quick look around the museum (the best I can reconstruct it), starting with a nice photo of Mary Anne Sherwood with the Guyasticutus:

Then Joseph’s patented “Snow-Mobile” — then a cougar — then a complex exhibit:

Notice these guys at the bottom:

They remind me of Moore’s words earlier: “...bear skulls mounted in velvet…” (...) That’s all I got though. If you know of any more pictures, or descriptions, let me know… My internet copy of the Tribune article has a couple interesting-looking, but very-poorly-reproduced photos of the non-existent “stork”, a heron with a snake in its mouth, and a bear with a human baby in its arms. I would be especially interested in any pictures of the “night heron that looks like a penguin” or of the “three species of wolverine now thought extinct in Idaho”... But anyways, lastly, before moving on, it is important to remember the “fine timber wolf preserved in the same museum” — to remember, also, the obvious difference the Tribune noticed between this and the Guyasticutus… Here, it seems relevant to note that the Guyasticutus, if taxidermized in 1886 (13 years pre- Mary Anne, who also learned the art), must’ve been taxidermized very near to the beginning of Joseph’s career as a self-taught taxidermist. But anyways, continuing…

1948: The Tribune article opens with an imaginary scenario preceding Sherwood’s nomination of his so-called “Guyasticutus”, then points to a very similar word in Webster’s dictionary…

This is interesting to me because I have heard of this animal before. My friend Charlie told me about it a long time ago. He called it a “Sidehill Gullywump”, though, not a “Gyascutus”...

Also interesting: There is a genus of jewel beetle spelled the same, “Gyascutus”. It was identified and named in 1853, by John Lawrence LeConte, “the father of American beetle study”....

3: Gyascutus to Guyasticutus

Looking through the collection of newspapers at the Library of Congress Website, the earliest instance of “guyasticutus” I can find is in the Butte Record (Butte County, CA), 4/14/1855:

Second earliest is in the Raftsmans Journal, 5/23/1855:

Third earliest is in the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 1/4/1858:

Another interesting one is in the Weekly Pioneer and Democrat (Saint Paul), 9/2/1859:

But anyways… 1/15/1861, the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, point in a helpful direction:

So New Question now: What was “the celebrated Guyasticutus hoax”?

As is sometimes the case, dropping the middle syllable is the key… In early 1845, a sensational (probably completely fictional) account of the “Gyascutus Hoax” circulated through southern newspapers (word for word). Here it is as it appeared in the Liberty Advocate, Liberty, MS, 3/15/1845:

From here, it is not hard to understand the 1850’s senses and variations of the word. The southern political overtones of the story adhere: “Gyascutus” is a “Yankee”, and a “Whig”.... Then, as the Whig Party starts collapsing in 1852, the spelling splits into “Guyascutus”: “Guyascutus is crippled! Long live the stout Democracy of the Old Dominion!”.... Then it gains a syllable in 1855 = the “great guyasticutus”, who is the unseen force behind the NYC-based Know-Nothing Nativist Movement, also the bearer of the “cloven foot” that is peeking out from under the veil of emerging Republican Industrial machinations…

Also, as always through this phase, the word is a purposefully inscrutable word = the latin science-name for a “whatchamacallit” = the “Willapus Wallapus” = the name of any imaginary creature = the name of an impossible creature, with infinite and/or contradictory properties = the name of a hoax creature, that has obviously never existed, and/or, “Has escaped!”.... The word is ripe for association with any of these famous properties. A gyascutus, or guyascutus, or guyasticutus can be a made-up animal, an unidentified animal, a weird animal, an escaped animal, an escaped human, a homeless human, a “drifter”, a “tramp”, a lost knick-knack, an inscrutably hi-falutin’ knick-knack, an inscrutably hi-falutin’ nugget of info, a southern rube word, a freed-slave word, a nonsensical machine part, a tertium liquid, a flip-flopper, a con-artist, a con-artist’s scheme, an unseen force, an unseen beast, any beast, anything that is concealed, etc.. Into the 1860’s, as the South starts collapsing, as various Southerners disperse westward and etc.., such fluidity, political and otherwise, dominates American use of the word. See the Western Sentinel, North Carolina, 2/16/1866, where an editor mimic the prose of a “western editor, indignant at the usurpation of power”:

Later that year comes the first instance I can find in Idaho. It occurs up in Silver City, in this charming bit in the Owyhee Bullion, 12/20/1866:

Then so on from there… As the 4-syllable “gyascutus” persists in the memory of the famous hoax, the corresponding shapeshifter occasionally solidifies into the single imaginary animal that will be immortalized in the copy of the Webster’s Dictionary possessed by the SLC Tribune in 1948 (= the Sidehill Gullywhump). One was caught in 1883:

The 5-syllable “guyasticutus”, meanwhile, bounces around down a similar-heading, but not always-overlapping path. Associative fluidity very-slowly-evaporates, and metaphorical usages dry up. The word gradually congeals into names of increasingly literal circus side-show “freaks”.

6/18/1882, the Salt Lake Herald Tribune, emphasizes the difficulty of pronounciation:

9/12/1883, the Semi-Weekly Miner, Butte, MT, states an inscrutable statement:

4/4/1886, at the dime museum in Saint Paul, some racist undertones surface:

The show closes a couple weeks later. See Saint Paul Daily Globe, 4/17/1886:

Then comes back later that year:

5/25/1890, the Idaho Statesman continues in the valley-wide tradition of local newpapers’ publicizing of their not-mourning of the death of a “tramp printer” [see SALT CHUNK MARY]:

Then so on from there…

As we enter the 20th Century, we encounter some interesting cousins of our Guyasticutus Ringdocus — cousins illustrized, cousins vegetablized, cousins nominized, and cousins taxidermized :

((Compare the eyeballs of the Lion of Gripsholm Castle.))

In 1909, in a nice bit from the 38th Chapter of his Reminiscences: Incidents in the Life of a Pioneer of Oregon and Idaho, Boise’s own William Armisetad Goulder [see GOULDER, W.A. — also ATLANTA KATE] briefly discusses another Northwestern Guyascustas from sometime way back:

Passing through a good strong belt of timer we reached another open glade, where Grasshopper Jim built a cabin and where he maintained and operated a chicken ranch. Grasshopper, as we all called him, was quite a character in his way, who had at one time figured prominently in the history of Oregon. He was the man who caught in the woods near Oregon City a terribly ferocious and nondescript wild beast, known everywhere now to naturalists and showmen as the Guyascutas. Jim caught this animal alive and partially tamed him, sufficiently so for exhibition purposes, when one night in Oregon City—--but no !! I will not tell this story until I can hear from Jim, hoping that when I do hear from him he may be in Heaven. I heard a lady one evening in Oro Fino say to Jim, “Mr. Grasshopper, you are a daisy most every way, and everybody likes you, but I want to tell you, you are entirely too extravagant in your ideas.” This was poor Jim’s only fault. Peace to his ashes, if they should prove to be real ashes.

Note that, at this time (1909), its name is “known everywhere now to showmen and naturalists”....

Note: By 1958, its name will be forgotten by everybody, everywhere. In the Evening Star, Washington DC, a man named Charles E. Tracewell uses this fact as his basis for a complex argument:

4: Guy Fawkes to Gyascutus:

Going back further now (from 1845), there remains the question of from where came this word, “gyascutus”. For starters, it is not latin. Other than that, I cannot say for sure, but think I have a pretty good guess…

Consider some interesting American words originating in the middle quarters of the 19th Century: hifalutin, skedaddle, cantankerous, goshbustified, dumbfungled, honeyfuggle, hornswoggle, blustrificate, absquatulate, explatterate, bloviate, obfusticate, discombobulate… [See also the bit on the “SOCKDOLOGIZING OLD MAN-TRAP”, in IDAHO (THE WORD: 1860-1876).] These are self-consciously “American Words” — “American-style Words” — “Mississippian Words” — “Kentuckian Words” — words “partaking in that bombastic and unusual character typical of Western eloquence” (William Henry Milurn, 1860). They were usually popularized in plays written by 19th Century Englishmen (Our American Cousin, etc.) , backwoods tales written by big city east coast newspapermen, and etc..

My general guess is that “Guyasticutus” belongs to this group of words, and that it should be understood in basically the same way: as an “American-style” bombastification, recombobulation, and/or semi-intentional dumbfungling, of some hifalutin bit of English vocabulary. Note, for instance, how the transition from the “obfuscate” to“obfusticate” is reflected in the transition from “gyascutus” to “guyasticutus” — how, in both, the injection of the extra syllable (“ti”) serves to further obfusticate the obscureness already obvious in the word…. The only difference: One is an obfustication of a “real obscure word” = a proper English fancy word. The other seems to be an obfustication of a “fake obscure word” = a backwoods-style science word, taken from some sort of proto-Pig Latin.

My more-specific guess: GUYASTICUTUS comes from GUY. Like, in roughly the same way that SOCKDOLAGER (= a ‘Knock-Out Blow’) bombastifies the England verb, “to SOCK” (= ‘to punch’), GUYASTICUTUS pseudo-scientizes/latinifies the England noun, GUY. (...)

For this guess to make any sense, it is important to recognize that, in 19th Century times, this word, GUY, did not mean everything it means now. See, for of some usages, The Love-Match, by Henry Cockton, 1845:

“Miss Majoribanks”, by Margaret Oliphant, in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 1865:

And One White Violet, by Kay Spen, 1869:

In short, in its mid-19th Century sense, the word meant an absurdly-dressed person. The idea seems to come from a specific feature of London’s Guy Fawkes Day celebrations: Every fifth of November, on the anniversary of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot, a dummy was made of straw and dressed to resemble Guy Fawkes (wearing cloak and carrying lantern), then carried through the streets by singing boys, then burnt in big fire at the center of town. This dummy was referred to as a “Guy Fawkes”, or a “Guy”. Here is an illustration from 1826:

Illustration is from William Hone’s Everyday Book, or, A Guide to the Year, 1826. It is accompanied by some commentary:

(...)

As far as I can tell, the earliest preserved instance of this specific association (a “guy” = a person who is dressed like a Guy) is in Elizabeth Hamilton’s Memoirs of Modern Philosophers, Dublin, 1800:

Novelty here is indicated by an explanatory footnote:

Which makes sense…. In the 200 years following his 1606 execution, the bodily properties of the original human version of Guy Fawkes reduce in the popular memory down to two: carrying a lantern + wearing a cloak — these which can then be reapplied to any vaguely human-shaped form to create a recognizable resemblance to Guy Fawkes = a re-personified “Guy Fawkes”, or “Guy”, for short… = a pretty absurd looking human-form = a lumpy straw-man, stuffed into an old cloak and carrying a lantern….

The jump is easy to imagine: ‘looking like a Guy’ to being quite a Guy.

Worth noting are certain peculiarities of Victorian-era bourgeois fashionionability — how these might relate to the anxieties (“looking a guy”, etc.) that accompanied the advent of Victorian-era bourgeois fashionability.

In caricatures from the era, we see fashionable bourgeois women often depicted as strange new sorts of creatures:

From here, it is not especially hard to imagine some wordsmith’s leap from GUY to the mid-19th Century GYASCUTUS… A plausible “initial idea” for the new word is that it means not a person who looks like a Guy, but a freshly discovered sort of creature that is, in itself, a Guy = not a person who looks absurd in their newfangled fashions, but a new sort of pseudo-scientific animal that is, in itself, absurd.

(...)

5. For Summary:

The reason he looks so strange is because he is transforming into a wolf. Process (central London to the northeastern SRP) is like: The original GUY FAWKES (actual guy, with cloak and lantern) to a GUY FAUX (straw-man, with cloak and lantern) to a GUY (abbreviation) to a GUY (person who looks absurd, implausibly costumed like a Guy) to a GYASCUTUS (creature who is, in their nature, implausible / so absurd as to be impossible, unencounterable, extinct, escaped, a hoax, etc..) to a GUYASTICUTUS (who is even more absurd, even more obviously hoax…) to various literalized, animalized, and personified freakshow versions of the GUYASTICUTUS (obvious “frauds” = animals or humans more-or-less made to look like the imaginary non-image of the famous GUYASTICTUS) to our own the GUYASTICUTUS (bad wolf mount, named by Sherwood, who probably knew what he was doing) to the RINGDOCUS (mispronunciation of Sherwood’s name for his bad wolf mount / forgetting of the joke) to “a mounted example of a SHUNKA WARAK’IN” (association of Sherwood’s bad wolf mount with Ioway legends of a mysterious species of wolf). Surviving side-branches are the Jewel Beetle, genus “Gyascutus” (1853), and then the ones that bring to us the more-nowadays senses we attach to our word, “guy”....

For more of the Montana story, google “Ringdocus”, or “Shunka Warak’in. There are some monster-wiki’s and etc. — some two minute clips from History-Channel-type documentaries sensationalizing events leading up to the 1886 shooting of this genetically-mysterious wolf-pig of the Madison Valley. If Sherwood is mentioned at all, his role is assumed to be inconsequential. Most complete treatment is a nine-part reenactment/documentary, produced in 2009 by students at MSU, called Ringdocus: Legend of the Shunka Warak-in…. Most pro-Montana treatment is a 2007 article in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle, “Mystery Monster Returns Home After 121 Years”…

I might do a separate entry on this: “the upper midwestern United States” = the place where “Iowa” and “Idaho” are basically the same place.

The mount is now housed at the History Association’s Museum in Ennis, MT. It was found in 2007, by Jack Kirby, another grandson of I.A. Hutchins, in the basement of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, in Pocatello. Apparently, after the Sherwood Store/Museum closed, all specimens and exhibits were donated to there.

This is wonderful