CHEWING THE SCENERY

---------

CHEWING THE SCENERY

Chodoriwsky points us to this bit in the TDF’s Theatre Dictionary — entry “Chewing the Scenery”, at tdf.org:

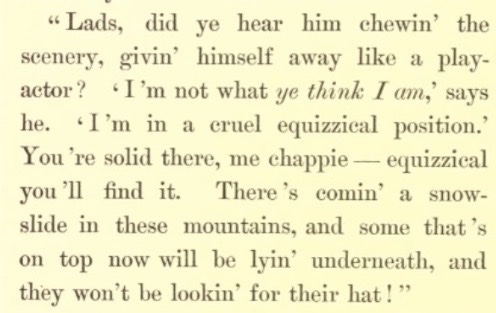

Although the phrase “chewing the scenery” is sometimes attributed to noted wit and critic Dorthy Parker, who observed that a particular actor was “…more glutton than artist…he commences to chew up the scenery” in a 1930 review, the expression was actually coined long before. The earliest published occurrence seems to be in Idahoan novelist Mary Hallock Foote’s 1894 story COUER D’ALENE, in which one character disparages another by saying, “Lads, did ye hear him chewin’ scenery, givin’ himself away like a play actor?” And since COEUR D’ALENE is about miners, not actors, that implies it was already common usage.

(…)

MORE CONTEXT — QUESTIONS — ETC.

The story is about 40,000 words = a “novella” by nowadays standards… Says Foote in 1895, one year after Houghton Mifflin and Company published it as a book in Boston, “The book to me seems too crude as a novel”. Here though, she’s talking more about the book’s content = a little melodrama of Victorian manners set inside the Coeur D’Alene Labor War of 1892…

First Chapter is a manners-puzzle: A vulgar Irishman and a polite Londoner are sitting in their one-room prospectors’ cabin in the woods in North Idaho. It is night and storming outside. Then in bursts a pair, requiring refuge and a change of dry clothes: The one who requires the clothes is a young lady recently arrived from New York City, who is polite — the other is her father, who is the manager of the nearby Big Horn Mine, and who is very drunk, and who collapses immediately into imperturbable sleep. How is the scene to be navigated politely?

Second Chapter is called “An Equivocal Position”: Back at the Mine Manager’s residence, the servants and their miner-friends are whispering in the shadows outside, not smoking, being secretive. Then the two polite ones from the cabin arrive out of the woods. They converse in the moonlight, unaware they are being overheard. Having successfully navigated the challenges of the previous chapter, they are in love now. (“Life on the Frontier”, Foote notes, “is remarkably productive of such perilous short-cuts to sudden intimacy”.) They are parting politely when the man from London outbursts:

A thing is bothering him, but he won’t say what. He just keeps going on like that, being like, “I am not what you think I am!” — and like:

I did you unconscious injury before I knew of your existence. I am in a cruelly equivocal position.

Then the two part, both agreeing he is being mysterious. The Young Lady from New York goes up the stairs to the residence and the Man from London rides off into the woods. Then silence. Then a stir in the shadows. Then voices:

Generally though, the voices agree: there is evidence enough now...

Then so on from there: The voices are correct. Though not a Pinkerton, the man is the son of a prominent London Capitalist. The man is here on behalf of the London Faction of Investors invested in the Big Horn, spying on the New York Faction of Investors also invested in the Big Horn, as represented in the Big Horn’s current management, still passed-out-drunk back at the man’s pseudo-prospector’s cabin. The man has already learnt that this manager has dissolved into a puppet of the Miner’s Union — that the Big Horn has been completely taken over by the Miner’s Union. The man is about to report so back to London when his new romance makes him question what he is doing here, “among the holes and corners of the earth”. The man hesitates to send his letter, causing big problems for himself as the letter inevitably falls into the hands of Labor, who does not hesitate to weaponize it against his new romance: Learning that he is spying on them, the young lady of the New York Faction questions her earlier perception of his politeness. Learning that she has learnt the contents of his unsent letter, the man from the London Faction assumes she was the one who opened it and, thus, questions his earlier perception of her politeness. The two fall out and the forces of Labor upsurge — Violence and Explosions — these which force the two back into each other’s arms as, fleeing through the mountains, to the shores of Lake Coeur D’Alene, the cosmos itself reflects the plight their good manners spun westward, through the “Great Idaho Game” ...

Meanwhile, the Army of the USA is arriving on the scene — is obliterating the Miner’s Union. And the victory will be cause enough for a grudging truce between the New York and London Factions. The polite Londoner, whose name is Darcie, will be married to the polite New Yorker, whose name is Faith. Together, they will return to the Coeur D’Alenes so that Darcie can be the new manager of the Big Horn. The End.

Then so on from there: 1894 would be the last of Mary Hallock Foote’s 10+ years in Idaho. She was by this time a popular writer and illustrator, with a devoted readership back on the East Coast. Foote was from the East Coast — went to college in New York City. The title given to her posthumously published “Reminiscences” (1972) sums up her situation well: A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West… She lived and worked in a beautiful lava rock house upriver from Boise while her husband, Arthur, and his company, The Idaho Mining and Irrigation Company, did the initial work for what would become the New York Canal Project. 1895, she would leave for Grass Valley, CA, so that Arthur could be a Mine Manager there. 1899, there would be another Labor War in the Coeur D’Alenes — this one bigger, but basically the same... The Western Federation of Miners, formed in the wake of 1892, would uprise against the Mine Owners Association — would blow up a bunch of gear, seize some control of the region, and then get immediately squashed by the US Army. Foote’s Coeur D’Alene (1894) would be serialized in the wake — redistributed through various newspapers across the nation. And the same in 1906, in the wake of the assassination (?) of ex-Governor Steunenberg, through the ensuing “Trial of the Century”, as the leadership of the Western Federation of Miners was unsuccessfully prosecuted for some sorta pointless vengeance for 1899 (?)… Since then though, nobody has read the book. Even when Stegner’s Angle of Repose (1971) (a phrase which Stegner learned via Foote / a book which takes heavily from Foote’s life, unpublished letters, and reminiscences) renewed a little interest in this forgotten author, general assessment has ranked Coeur D’Alene (1894) as probably her worst book. Which is understandable… Among her subtler and more-perceptive books, this book is easily dismissed as not-so-subtle propaganda… Which it is….1 Professor Maguire is not wrong when he writes in 1972 (Mary Hallock Foote, Vol. 2 in Boise State College’s Western Writers Series):

I still liked it though… And I thought the wooden stereotypes were still interesting, too — came off deeper than just “wooden stereotypes”...

Say instead: “Lizard Imposters”.... Like, though clearly intended in the shape of a Romeo and a Juliet, the heroes here are unsubtle lizard imposters of those star-crossed aristocrats. This tale of the triumph of their weird priorities over the grievances of Labor is pure nonsense. But it could’ve been no other way… Also, the book is wonderfully written — totally readable, despite its being of pure nonsense…

A simple argument for the book’s significance — five points:

Say: “History is written by the winners”.

Say: The winners of “The West” are various conglomerations of non-resident capital (here portrayed as rival factions of New York and London investors invested in a particular Idaho Silver Mine).

Say: The basic problem of the Romance of the American West is that when depicted in the context of their own winning of it (out West), the winner does not personify very plausibly. Traditional methods of romanticizing them do not work anymore. Non-Resident Capital just comes off like lizard people.

Say: This book—Coeur D’Alene (1894) / its trials and its tribulations of its Lizard Romeo and its Lizard Juliet, as situated inside the wildness of Idaho, inside the sinisterness of the machinations of their own insubordinate Western Labor Force---makes the clearest illustration of this basic problem. The book should be understood as the representative product of a sort of “first try”, or “phase one”, or “primordial mode”, in development of the Romance of the American West. It is the book that reveals the basic problem.

Say: Thus comes the definitive feature of all subsequent Romance of the American West: the way it solves its basic problem…. Like: Looking around here now, post WW1 and beyond, it is not hard to see what they did. Across the Romance of the American West 2.0, there appears a mysterious absence of Employers. That is the whole trick. Like: Unable to plausibly personify themselves here, the winners have simply written themselves out of history here — have replaced themselves and their employment of their westernmost employees with a re-romanticized Spirit of the American West = the Freedom and the Individualism of their westernmost employees… It is how you get, for instance, “The Cowboy”: You subtract all the Cattle Barons and the RR Interests which are wielding him, then deduce that the reason he is out here working the range is, like, Freedom. Same with “The Trapper”: just subtract the international corporation that is employing him and focus instead on the adventure he is having. Same with “The Miner”: Extract him from the silver mines, where his employment is not dissimilar from that in the “dark satanic mills of Europe”, then re-picture him as a self-employed placer miner, forever forty-nining to new streams in new mountains in the sunshine with nothing but his shovel and his foolish dreams and his denim pants.

[See QUARTZ ON THE BRAIN]

[See NON-RESIDENT CAPITAL]

(6th Point? — 2 )

But anyways, admitting that this still might be her worst book, a broader argument could be made for Foote’s own personal significance. Coeur D’Alene (1894) was not her style. In the same way she rejected the book a year after it was published, she rejected all such dramatizations, or summarizations, of “The West”. Not surprisingly though, those were two things she tended to do. If her Coeur D’Alene (1894) is her great dramatization of the essential absurdity of “The West”, then her three-page intro to The Last Assembly Ball (1888), is her great summarization. She advises here an atomized approach — an “episodic manner”:

[see FOOTE]

(...)

But anyways, getting to these words now: “chewing the scenery”...

If they look strange, their meaning is still clear. Foote has added “like a play actor” to make sure we get it. And there’s double ‘dramatic irony’ here, too: Darcie and Faith do not realize they are on stage, with an audience in the dark. Then they exit and the audience reflects: ‘what a ludicrous theatrical performance’... The audience then recontextualizes this theatrical performance in a way that would make sense of its theatricalness: ‘The actor, who is so obviously acting, must be a spy’…

In all, lots of interesting language from the mouths of the under-class. And this scene gives it in its pristine-est presentation: pure talk, as emitting from a disembodied servant/miner-combo in the dark — at one point even literally reflecting the upper class talk:

I am in a cruelly equivocal position ⇨ I’m in a cruel equizzical position.

Note: The voice understands the meaning of the word, just not how to say it right. And arguably, “equizzical” is the better word anyway — a nice folk-correction of the etymologically-awkward “equi-vocal”. Either way though, if this version of the word was ever in any common usage, or was taken from any real-life mispeak, Foote’s is the only surviving record of it. To me, it seems too perfect . I’m guessing Foote made it up herself, special for the scenario. Only about 60/40 on this though…

Note: This sole instance of “equizzical” comes three lines after “chewin’ the scenery”, and is immediately followed by a nice “snow-slide” = ‘The Revolution’ metaphor — then is finished with these other words which I have not yet figured out:

….turnin’ his chin loose about his mash....

Note: For another excellent Idaho-word-mystery from Foote, see The Chosen Valley (1892) — see HORNIQUEBRINIQUES….

Note: I’ve read that Foote had a good “ear” for everyday talk in Late 19th Century Idaho. I’m not sure, though, that that’s entirely what’s going on here... Or in other words: I don’t think Foote is reproducing Late 19th Century Idaho’s Miner-Vernacular in the same way we, on the opposite side of the 20th Century, imagine authors reproducing vernaculars. We imagine authors of vernaculars working bottom to the top — gathering quirks and particulars from a particularly quirky vernacular, assembling them into dialogue and, in this way, making a bigger picture. We read a weird phrase in a book about Late 19th Century Idaho, written by a Late 19th Century Idaho author, and we assume that the weird phrase is from Late 19th Century Idaho, more or less — either originated there, or at least passed through somewhere within earshot of the author…. In this way, we imagine the author listening. We do not imagine them doing that other thing authors tend to do, which is reading. And the difference would be especially outstanding in Late 19th Century Idaho — and then even more for a Victorian Gentlewoman here. Excluding the Idaho Statesman, none of Foote’s reading material would’ve been coming from Idaho.

Note: My guess is that this is from where Foote got “chewing the scenery” : her reading material — probably some east coast periodical…. Only about 60/40 on this though…

(…)

ORIGINS:

Searching through the books collected at googlebooks.com, Foote’s use is the first use I can find in fictional literature. Same year though, 1894, there appears three non-fictional variations in a book called Pickings from Lobby Chatter, picked by someone calling themselves “Ah There”:

“Ah There” was a man named Al Thayer. He was the theater columnist for the Cincinnati Enquirer — wrote a theater column there called “Lobby Chatter”. His book was put together by him picking his favorite bits — these which would’ve been published sometime before 1894.

So going now to libraryofcongress.org, searching the pre-1894 newspapers collected there, I find the phrase and its variations all over the place. See for instance, the reminiscences of the great John Ellsler3, as printed in the Omaha Daily Bee, 5/25/1890:

It was the time of a big theatrical revolution, which started with the light bulb, which arrived in theaters across the 1880’s, revolutionizing stage-lighting techniques and, in turn, revolutionizing stage-acting techniques as the “new style” adapted to the new lighting conditions — as the “old style” didn’t.

A good analogy is the microphone — how, with the microphone, the stage-singer does not need to manually project their voice to the back of the room anymore — can whisper through the microphone to the back of the room now, Sinatra-style…. So says Ellser, “easier manners are required”: The difference between old and new styles is the difference between operatic and crooning styles. The “scene chewer” means the hangover of the manually-projected style — means the one who is now singing operatically into the microphone — the one who is now shouting into the microphone — the one whose facial contortions and wild gesticulations, necessary to cut through the former dimness, are over-amplified through the new light.

Interesting to note: The light bulb precedes the movies. And once adapted to the light bulb, the 19th Century Theater Actor is pretty-well prepared for the movie camera — for the Big Screen — to be a glowing and twenty-foot-tall version of their face on the Big Screen… See Like: Basically, the technologically amplified “new-style” is already movie-style-acting — suppressed, subtle, etc… Of course some adjustments will be necessary with the advent of movietechnology, but these adjustments will be relatively insignificant. “Theater Acting”, originally self-amplifying, is already transformed. ((Exaggerizing into Subtletizing.)) From here, adjustments are only quantitative. With advent of Big Screen Technology, for instance, the additional amplification requires corresponding increases in “subtlety”.

Also interesting: Last echoes of the rhetoric of the theater’s Light Bulb Revolution will be in the film-theories of Robert Bresson, Notes of the Cinematograph, 1975. Here, Bresson is hypersensitive to even the slightest residue of theater acting — its “grotesque bufooneries”, he says, still manually projecting themselves from the Big Screen…. Thus says Bresson: It is the task of the “cinematograph” to resist this “terrible habit of theater”. Acting, and Actors, must be eliminated altogether. A glowing and 20 foot tall face must not do anything. Already, “a single look lets loose a passion, a murder, a war”... Such is the power of the cinematographed “Model” (in place of the old actor: a cinematographed human, or donkey, or etc.. = “two mobile eyes in a mobile head, itself on a mobile body”): The model’s subtlety is monotonous and absolute.

The thing that matters is not what they show me, but what they hide from me and, above all, what they do not suspect is in them.

Contrast Thomas W. Keene, the greatest (and probably the first) of the Late 19th Century Scene Chewers….

He is “eminently pictorial and fills the eye with his presence”.... So says the Dallas Daily Herald, 11/6/1884, reprinting a bit from the “Star”:

Also the Wichita Daily Eagle, 3/22/1885, reprinting the same bit from the “N.Y. Star”:

Ten things to note here:

First: The Star is an NYC Newspaper, 1868-1891, struggling financially and running once weekly in 1884 — relatively obscure… The clipping was probably not spontaneously reprinted five months apart, between Dallas and Wichita. More likely, the clipping was sent by Keene himself — was sent to promote an upcoming performance.

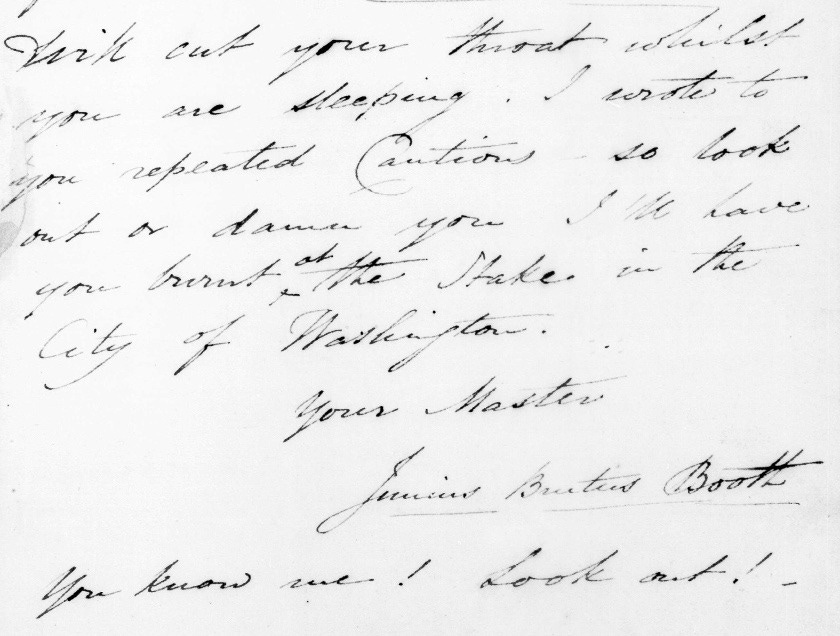

Second: “Vague and weird stories have been told about him”.... Here, Keene seems to be styling himself after the great Junius Brutus Booth — famously intense on stage, famously insane off stage. It is a theater cliche that lives on to this day. Nobody touches Booth though…. See, for instance, this letter Booth wrote to President Andrew Jackson, 7/4/1835….

((Reads:...will cut your throat whilst you are sleeping. I wrote to you repeated Cautions — so look out or damn you. I’ll have you burnt at the stake in the City of Washington. — Your Master, Junius Brutus Booth — You know me ! Look out ! ))

He was father of Edwin Booth, who was the Greatest Actor of the 19th Century, and who had “an abiding fear of ivy vines and peacock feathers” — also John Wilkes Booth, who was even weirder, even vaguer… All were well past their prime by the time Keene showed up.

Third: Dallas and Witchita… At the time, these were not the major theater-centers of the USA... Keene’s success was away from the sophisticates…. Old style was “country style” — was “western style”... Which makes sense… Like, when you go just once a year to the Theater, you go for the “Acting!!”, for the “Theater!!” — definitely not some re-definition of what ought to be such things.

Fourth: Light Bulb Revolution occurs abruptly across the 1880’s, simultaneous with Keene’s peak. The secret center? Though not typically performing in the Big Cities (running away from electric light?), Keene makes the perfect straw man for the Big City critics. See the San Francisco Wasp (quoted by way of Woods’ “The Survival of Traditional Acting in the Provinces: The Career of Thomas W. Keene” (1982)): Keene…

…is not an actor…and lithographic advertising cannot make him one.

Fifth: Again, very abruptly…. Though non-overlapping for sure, the Light Bulb Revolution is mostly complete by the time of the Couer D’Alene Labor War of 1892… Keene’s Richard III, meanwhile, is finally winning over Big City critics — is now provoking all sorts of sophisticated nostalgia for that lost Boothian breed of “Mad Tragedians” — is, in this way, inspiring the birth to a whole new generation of “Scene Chewers”.…. Also, Keene has noticeably “mellowed his methods”... See the Idaho Statesman, 4/13/1893, by way of “New York, March 15” — printed under the headline, “GREAT DECLINE OF TRAGEDY”:

Sixth: “He was said to chew the scenery”... This vague and weird story (as reprinted in 1884 Dallas and 1885 Wichita) is the earliest instance I can find of any “chewing the scenery”.

Seventh: The other vague and weird story here: “...to carry a cake of brown soap in his mouth…”... Hard to imagine this one working so good….

Eighth: ‘Fighting and biting, yet amiable the lascivious pipings of a lute in a lady’s chamber’…. Good description here of what will become “chewing the scenery”... But the words are not yet meaning that. What they mean is actual chewing of scenery.

Ninth: “...to work up passion”…. Direct connection is made here between Keene’s off-stage stuff and his on-stage stuff. The off-stage madness is ‘working up’ to the on-stage dramatics…. It is ‘part of his method’… Contrast the earlier “Mad Tragedians”, where no such connections were made — or at least not so directly…. Connection was more metaphysical, at best (genius and madness and etc)…. Junius Brutus was an outrageous alcoholic, and everyone knew it. No-one supposed his antics were ‘part of his method’. Occasionally, it was suggested that he might be faking to generate publicity.

Tenth: Whether this vague and weird story is a true story, I cannot say. Either way though, it seems like the key. The initial jump between this NYC paper’s ‘connection’ (off-stage scenery-chewing works up to on-stage dramatics) to the later equation (off-stage scenery-chewing = on-stage dramatics = “chewing the scenery”) is not hard to imagine. The jump could be made in the boonies, by an audience coming out to see this guy who the newspaper says chews on the scenery. It could be made by some NYC sophisticate, making fun of the Boothian pretensions of the residual old-school. It could be made within the theatrical industry itself, naming its old style and/or just mocking one not-particularly-respected peer. Either way, there could be something there for everybody. Whether the phrase actually moved between the three groups, though, is hard to say. Like, if we imagine the phrase surfacing in east coast theater circles, it is hard to imagine its way to a North Idaho Mining Camp. Not impossible though…. The People who lived in North Idaho Mining Camps in 1892 were not from North Idaho Mining Camps. They were from all over the place.

(...)

BACK TO FOOTE:

The gap between theater jargon and “common usage” is not a big gap. It is nice to be dramatic — nice to act like “the world’s a stage” — nice for everyone... So again, only about 60/40 here: I know Foote did not make the phrase up. I think she did not hear it anywhere in Idaho — think she probably read it in some periodical published somewhere else….

The three sources of Interesting Words and Phrases in the Idaho Books of Mary Hallock Foote:

Things She Heard (or read Idaho Statesman) In Idaho — “Horniquebriniques”

Things She Made Up in Idaho — “Equizzical”

Things She Read in a Book Or East Coast Periodical in Idaho — “Chewing the Scenery”(?)

Also, to be clear: I don’t think this question has much to do with any question about the authenticity of Foote’s North Idaho Miner Talk. Regardless of the particulars, regardless of her “ear” for it, I think she has a good “idea” of it. And this idea would’ve been learned through some experience, too… I think of the famous Tolstoy line about happy families and unhappy families… Same difference: All mine-owners are coming from the same town (= the town where all the Cosmopolitans are citizens of). All miners, meanwhile, are coming from different towns — are speaking differently from each other… This is the whole romance of Coeur D’Alene (1894): The wilds of Idaho are the tunnels of Babel — a dark and vernacular disaster-area through which two mine-owners from different continents discover that they are speaking the same language — the language of the surface of the earth, of the daylight, of reason, civilization, good manners, and etc… Though not especially believable as a Romance, the underworld vernacular here comes off good. To accomplish this, I guess, Foote’s focus was less the specifics of Miner Talk, more the diversity, the distinctness, the vagueness, the weirdness of Miner’s Talk.

This is how I would explain the occurrence of the words, “chewing the scenery”, in one of her miner’s mouths: She used whatever materials were available to her — real life miner’s mouths to her imagination to stuff written in fancy periodicals back east — took vague and weird words and phrases from wherever she could get them out here.

But either way…

(…)

Here it is in its paragraph one more time:

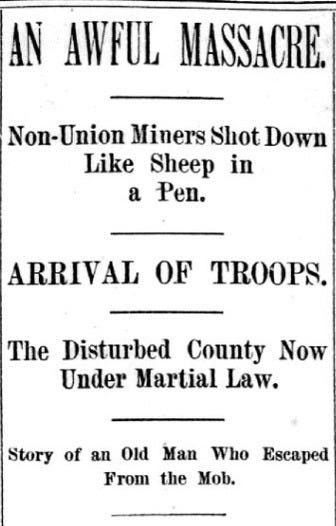

Particularly propagandous is the finale of the book, which centers around Foote’s fictionalization of a non-fictional occurrence which was, it turned out, not a non-fictional occurrence... 7/14/1892, Foote, living outside of Boise, read about it in the Idaho Statesman:

7/15/1892, next day, Foote read the Statesman‘s admission that the reports of the previous day had been exaggerated and that, actually, there exists no evidence of any union massacring of any non-union miners…. In the book, Foote processes this artfully — concludes:

Like: Such is the conspiracy between the lawlessness of the wild and the wildness of Labor: the latter to do crimes while the former swallows up the evidence — both, together, unequizzically contrary to the wildernesslessness of the Cosmopolis.

Also Note: We see the same idea (Labor = Lawlessness) repeated on the Steunenberg Monument in front of our Capitol Building: The statue is dedicated 1927 to Steunenberg / “Law and Order”, in commemoration of Governor Steunenberg’s stand against “Organized Lawlessness” (= Organized Labor) in the Coeur D’Alene Labor War of 1899 …

And so on to today? A sixth point here could go on for a while…. Wordchoice has set me up for some discussion of the “lizard imposters” which so many of our fellow Idahoans are now perceiving in our elected “representatives”…. So Say Like: A great irony is forming around us in the New Millennium — is forming into the form of a supposedly urgent political project to rescue the Freedom of the Cowboy from the Lizard Imposters who have taken over Our Representation in Our Government…. What is at stake here is, at best, nothing: The “Freedom” (of the old western employees) and the “Tentacles” (of the old western employers) are the same non-personifiable thing, just non-personified in different forms. The Cowboys are just being its little bitches, like they’ve always been. They’re just being more “political” about it now. Etc. Etc.. [see COWBOY — see Idaho’s new CHEAP TEXAS KNOCK-OFF POLITICS]……. Or in other words: This is the same problem all along = the inhumanity of our original western Romeo, which Foote so excellently revealed in 1894. And it is resurfacing now for understandable reasons, as our non-personifiable hero is outgrowing even its spirit-form. (……) See also Marx here — his stuff about “Monsieur Capital” = “The Capitalist” = the one who Marx elsewhere describes as “Capital Personified”…. (…) I can’t remember where, but somewhere, Marx makes an increasingly relevant point about how the Freedom of the Free Laborer is entirely contingent on the personifiability of Capital. Like, obviously, Free Labor has no freedom about its Lifetime of Labor. That is as mandatory ever. What we mean when we say “Free Labor” is a “Labor” that has some power to choose its employer. This Freedom is real, though, only insofar as Capital really is personified — is manifested through some multiplicity of human employers (distinct personalities and etc.) to choose from. Otherwise there would be just a monolithic and inhuman and inhumanly intelligent ‘Capital’ (= a value which is more valuable than itself = money which is worth more money) — this which would be infinitely Being Itself at the expense of human bitches… So a delicate thing…. Regardless of whether such personification is even possible (whether labor’s Freedom in this style can be anything other than ‘an illusion’), the recurring issue has been an issue of plausibility…. Clearly nobody is buying it now, but then the conspiracists believe that this is only a recent issue — that, sometime in the recent past (since whenever it was when the Cowboys were Free), some sinister entity must’ve hijacked the humanity of the forces employing us for the sake of their own infinite augmentation. (….) See again NON-RESIDENT CAPITAL… For Foote, this was the central mystery in the development of the Gem State. (…) The words were not invented by her — were a mystery often discussed in the papers, too (…) The mystery was the manner in which Non-Resident Capital was residing and/or non-residing and/or coming and and/or going through Idaho…. (…) Is it Good? Is it Bad? (…). As always, Foote has the best sentence — The Chosen Valley (1892): Non-Resident Capital is skittish. (…) The sentence equates Idaho’s Development with maneuvers typically associated with trying to catch (or scare off) a lizard. (…) See also the feeling we feel throughout Couer D’Alene (1894), where our Original Heroes of the Idaho Wilderness, for all their civility and etc., are not-quite-explicably “skittish”…

With John Wilkes Booth, Ellsler was co-owner of “Dramatic Oil” = an oil company in Pennsylvania in 1863 which did not do so good — was a little ahead of its time in its anticipation of an Oil Boom. (…) When asked what he was doing, leading up to his assassination of the President (why he had not been acting lately and etc.), Booth would tell people that his Oil Business was booming — which it was not. (…) Also note: Ellsler was not a Confederate. Neither were the any of Booth’s theater friends and family. (…) Booth was not a “Southern Actor”. (…) It is a thing which Historians have had an impossible time of trying to get across: how confusing Booth was — how nonsensical Booth was… (…) Best (but maybe not most accurate) explanations hint at the nonsenseness of familial and/or theatrical traditions.

So much research goes into your conclusions and connections.

On a side note I loved the book, Angle of Repose, but Stegner should have credited her in a big way.

Deep Thinking: “This book should be understood as the representative product of a sort of “first try”, or “phase one”, or “primordial mode”, in development of the Romance of the American West. It is the book that reveals the basic problem.”