BLINKINGDOFFER

-------

BLINKINGDOFFER

1883, as the Oregon Short Line RR Company cut its way across the Snake River Plain, the word NAMPA appeared in black letters on a white sign next to a water tower next to the tracks in the sagebrush desert area of the Boise River Valley. It was the name the Oregon Short Line RR Company, subsidiary of the Union Pacific RR Company, was giving to its water stop there. Where the name came from, or why the Company had decided to apply it to this particular spot, was not explained.

Some new stops and sidings across the SRP, along the OSL, Pocatello to Pagari to Payette, 1882-1883:

A few of these (BANNOCK, SHOSHONE, WASHOE) were recognizable. They were, and still are, names of familiar Native American Tribes. The other 25, though, were not recognizable. People generally assumed they must be “Indian Names”. People did not know what they meant.

The subsequent development of the “meaning” of these names varies. In each case (1-25), the development of the “meaning” is proportional to the development of land surrounding the so-named stop/siding. The names are thus sortable into four sorts:

ONE: NO TOWN ⟺ NO MEANING :: The RR stop did not become the epicenter of a new community. Nobody was around in time to wonder what the name meant. No meaning was ever provided. The name soon vanished. See: CANO, KAMO, MAZA, TICESKA, TUNUPA, WAUCANZA.

TWO: FAILED TOWN ⟺ A SINGLE MEANING :: Some light early settlement in the area… Somebody, at some point, was around in time to wonder what the name meant. A single meaning was provided. Nobody stuck around long enough to question it —- or arrived to question it. Either that or the name was soon changed. TOPONIS (“black cherries”), for instance, was changed to GOODING, renamed for Frank Gooding, Governor of Idaho (1905-1909) and early developer of the area. See also: ARIMO (“name of an Indian Chief”), BISUKA (“not a large place”), CATA (“cinders”), KIMAMA (“butterfly” ), MORA (“mule”), NAMEKO (“drive away”), NAPATA (“by the hand”), OMANI (“to walk”), OWINZA (“to make a bed of”), PICABO (“come in”//”shining river”), TIKURA (“the skeleton of a tent”), WAPI (“an Algonquin word”).

THREE: SMALLER TOWN ⟺ “SOME DISPUTE” :: Some small, but successful settlement in the area… A single meaning was provided. Somebody, at some point, questioned it. One or two alternative meanings were provided. People failed to come to a consensus about which one is the true one. New meanings were then brought to the table as some difference of opinion ensued. In KUNA, for instance,

There is some difference of opinion about what “kuna” means. Some say that E.P. Vining chose the name from a Shoshoni dictionary, believing the word means “snow”; others say it means “the end”; and still others, “green leaf” or “good to smoke”.

((1 ))

See also: MINIDOKA (“well spring”//“broad expanse”), NOTUS (“its all right”//or in english, “Not us!”//or “an ancient city of North Africa”//or “the Greek word for the south wind”).

FOUR: BIGGER TOWN ⟺ “MUCH DISPUTE” :: Growing settlement. An initial meaning was provided. Somebody, at some point, questioned it. One or two alternative meaning were provided. People failed to come to a consensus about which one is the true one. Kids started making dirty puns and/or dirty meanings. Then a newspaper got involved —- fact-checked all these conflicting “local legends” by asking a person at Duck Valley and/or Fort Hall if there is a Shoshone word that sounds similar. In NAMPA, for instance…

Best account is Annie Laurie Bird’s 1965 piece for the Idaho Reference Series (NO.39 — “The Origin of the Name Nampa”). I summarize:

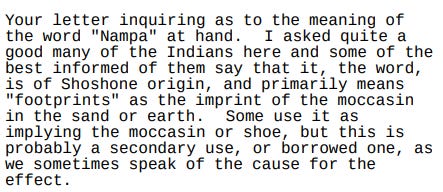

Already by 1911 the locals were “beginning to defile the name by ascribing to it putrid definitions and vile epithets in unfamiliar tongues”. Resident F.G. Cottingham took it upon himself to remedy the situation. He wrote to the US Indian Agents at Fort Hall and Duck Valley, asking if there was a Shoshoni word that sounded something like “Nampa”. Evan W. Estrep, from Fort Hall, replied:I am not able to find the meaning of the word ‘Nampa’, although the Indians seem to think it is a Shoshone word, Namb, a word very similar in sound, means ‘moccasin’.

George B. Haggett, from Duck Valley, replied:

And, so, Cottingham concluded….There may be some room for question as to whether the word now spelled is pure Shoshone, but there is no room for doubt as to whether the original root was a Shoshone word, and the meaning is either moccasin or footprint.

(( 2 ))

Then, in 1919, Fred Wilson, Secretary of the Nampa Harvest Festival, wrote to local author Fred Mock (author of “Blue Eye”, 1905, published under the pseudonymn “Ogal Alla”):We have decided that a stunt, new and different from anything ever tried here before, would be to seek out and find Chief Nam-puh.

Mock agreed. His performance as “War Chief, Big Foot Nampa” became a regular fixture at subsequent festivals. Then so on from there, as people forgot the performance / remembered that the word had something to do with an Indian Chief Big Foot / assumed that the name was in some way taken from that of “Bigfoot” and/or “Chief Nam-puh”/ grew gradually suspicious of this very-dubious-sounding etymology…… One alternate suggestion I have heard circulating in recent years is that the name is an acronym for the North American Meat Packers Association. The wikipedia page, meanwhile, goes with a qualified version of Cottingham’s conclusion —- says “may have come from a Shoshone word meaning either moccasin or footprint”... It is increasingly suspected, though, that the name is just meaningless.

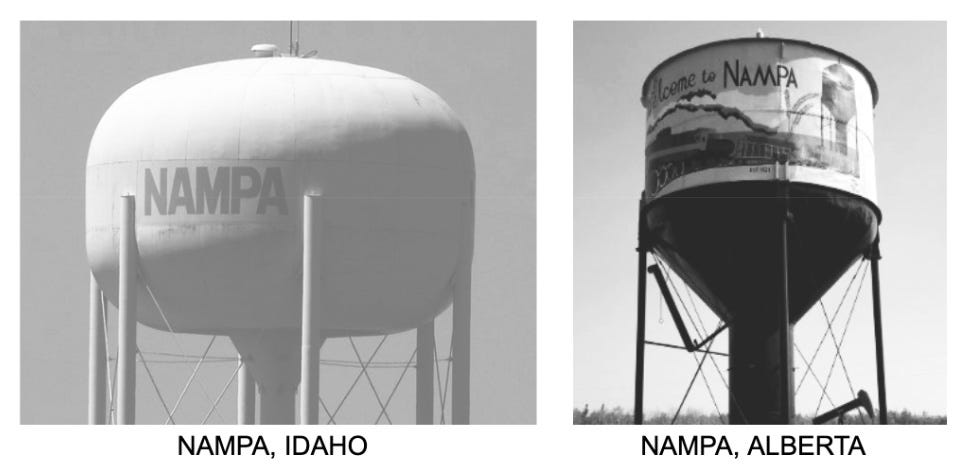

See also: NYSAA, in Oregon… And, also-also, for an interesting compare-and-contrast see Nampa, Alberta, Canada — 1400 miles due north from Nampa, Idaho, USA: The town’s origins are remarkably similar (non-flag-ship RR town founded by Land-Improvement Co. working in cahoots with the RR Co.). It just didn’t have the good fortune of being born between a Boise and a Caldwell. Its about a 2 ½ now. The wikipedia page says “an indigenous word meaning The Place”, but the local librarian is not so sure about that.3

See the water towers:

((4 ))

But anyways, looking in retrospect at these 25 points on a straight line through what was, at the time of their nomination, unpopulated sagebrush desert, it is easier to not get distracted by the historical peculiarities of this or that point. The more-obvious question is a question of the line that connects them — the “Oregon Short Line”. So…

Why did the Oregon Short Line RR Company name these names this way?

(...)

GENERIC ANSWER:

For starters, George R. Stewart (The Names on the Land, 1946) is correct:

The great majority of our present Indian names of towns are thus not really indigenous. Far even from being old, they are likely to be recent….Troy or Lafayette is likely to be an older name in most states than Powhatan or Hiawatha. The romantics of the mid-century and after applied such names, not the explorers and frontiersman.

See Idaho Towns named in the 1870’s:

See Idaho Towns named in the initial rushes of the 1860’s: SILVER CITY, RUBY CITY, IDAHO CITY, ORO FINO, ORO GRANDE, PEIRCE, DeLAMAR, ROCKY BAR, QUARTZBURG, PLACERVILLE, CRYSTAL, ATLANTA, DIXIE, etc.. More mining towns named after metals, white prospectors, and confederate stuff… This all joining some earlier French non-town names from the fur-times: PORTNEUF RIVER, PAYETTE RIVER, BOISE RIVER, LAKE COEUR D’ALENE, LAKE PEND D'OREILLES — some early American Names: FORT HALL, FORT HENRY, AMERICAN FALLS, BEER SPRINGS — some Early Mormon Settlements: FORT LEMHI, FRANKLIN, PARIS — Etc..

((((Note: In the North, with the initial goldrush to the North, the possible exception is FORT LAPWAI, established 1862, in the wake of the first goldrush onto the Nez Perce Reservation — established because of the tensions generated by the invading goldrushers — tensions augmented by the USA’s efforts to shrink the Reservation Boundaries to make space for the invading goldrushers... Official US explanation for its new Fort was that it wanted to make sure that there wasn’t violence “from either side”. The Fort’s name, meanwhile, probably came from LAPWAI CREEK (not vice versa), which was probably an authentic name used by the Nez Perce for the creek and/or the surrounding area. The Fort closed in 1884, 7 years after the Nez Perce War of 1877. Then in 1911, a town called LAPWAI was incorporated around the site of the old fort (probably named after the old fort). The Town is the current seat of Government for the Nez Perce Reservation….

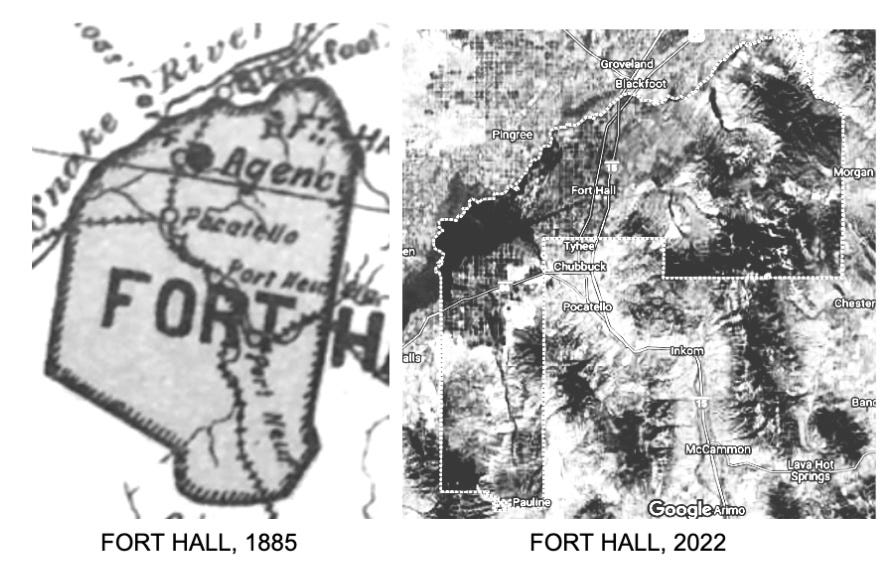

Note: In the South, with the initial goldrush to the South, the possible exception is BANNACK, established in 1863, which was the original name for IDAHO CITY. It was apparently named by incoming miners for the Bannack Indians they and their US Military Assistance were pushing out of the area so that there could be a goldrush to there. The town was renamed IDAHO CITY in February of 1864. The Bannock were officially confined to the FORT HALL four years later, with the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868. This was also when FORT HALL (the reservation 1868) was named for FORT HALL (the fur fort 1834). And so on to today: FORT HALL is currently situated between the towns of BLACKFOOT and POCATELLO on the I-15. It has shrunk considerably with the development of the Pocatello Metropolitan Area, which is centered around POCATELLO (the town established in 1890), which was originally centered around the Oregon Short Line RR Company station of the same name, which was established in 1882, which had previously been a Utah and Northern Railway Company station of the same name, established in 1878, one year after the Nez Perce War of 1877, same year as the Bannock War of 1878.

Note the location of Pocatello on both these maps — the other “Indian Names” (INKOM, ARIMO, TYHEE) which have emerged on the recent map, in the area that is not anymore contained inside the boundaries of FORT HALL….))))

For short: In the mid Century, the “romantics of the mid-century” were all living on the East Coast of the USA — not in Idaho. Though they may bear some responsibility for the name of the state itself (officially named in Washington DC 1863 (8 years after Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha (1855))), they do not actually arrive in Idaho until the Union Pacific RR Company brings them to Idaho. The Company’s 25 new “Indian Names” should be generally understood in this way: as a small part of this greater process, aimed as Eastern Big Capital, Eastern Potential Settlers, Eastern Romantic Notions and Etc.. — serving to help seduce all to what the Union Pacific RR Company (internationally financed, headquartered in Omaha) was then calling its “New West”.

Especially interesting here is a man named Robert Strahorn. He is head of the “Literary Department” for the Union Pacific RR Company, Envoy Plenipotentiary for the Oregon Short Line RR Company, and manager of the Idaho-Oregon Land-Improvement Company. Though I cannot find any evidence for his naming of these smaller stops and sidings, he definitely named some of the flagship stops on that same line (CALDWELL, MOUNTAIN HOME, maybe SHOSHONE?). And either way, it is not hard to see how 25 mysterious “Indian Names” would fit into the broader literary project of the Union Pacific here. See Robert’s wife, Carrie Adell Strahorn, on page 471 of her 1911 memoir, Fifteen Thousand Miles By Stage: She there tells us that the Union Pacific’s basic method of boostering its new destination was to be

…clothing it in attractive garb that it might coquette with the restless spirits in the East who were waiting for an enchantress to lure them to the great mysterious West.

(...)

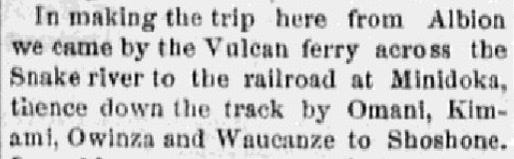

See the Idaho Statesman, 7/9/1885:

(...)

SPECIFIC ANSWER:

I first find it in Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary (1988) — in her entry there for BISUKA:

John Hailey, then librarian of the Idaho State Historical society wrote on 6 July 1915 that a Mr. Blinkingdoffer, chief engineer of the railroad, said he deliberately chose Indian names for the sidings and stations to avoid conflict with the names on other railroads.

I am intrigued. Boone’s source here seems to be The Biennial Report of the Idaho State Historical Department, Vol. 23, 1951. There is a nice article there by a man named Fritz L. Kramer, called “Idaho Town Names”. It gives a smaller dictionary of Idaho town names and, like Boone, uses the entry for BISUKA for some broader discussion about the weirdness of these OSL names. Kramer suggests that the occurrence of these “names of Indian (or possibly pseudo-Indian) origin” was not a mere coincidence. He then directly quotes John Hailey’s 1915 letter:

….when the railroad engineers were locating the route of the Oregon Short Line in 1880, 1881, and 1882. The chief engineer…was Mr. Blinkengdoffer (sic) whom I have met several times. He told me that he had given to all the railroad stations Indian names except at stations that were at little towns that were started and named before they located the road. His object in using Indian names was to avoid any conflict in names of railroad stations on other railroads.

Note the difference between Boone and Kramer’s spelling: BLINKINGDOFFER ⟹ BLINKENGDOFFER.

Kramer (that’s his sic, not mine) indicates a dubiousness, but he does not clarify what it is. A quick internet yahoo confirms the suspicion that it probably has something to do with this Mr. BLINKENGDOFFER. Nobody with that name has ever existed. And it looks like Boone’s BLINKINGDOFFER is not a correction of a misspelled BLINKENGDOFFER: Nobody with that name has ever existed either. So….

Who is Mr. Blinkingdoffer?

It sounds made-up. A tempting guess is that it must be Robert Strahorn. This would reconcile our “generic” with our “specific” answer, which, again, is always tempting…5 And anyways, in his position as head of the Union Pacific’s Lit. Dept., Strahorn would’ve been in good position to provide names for coming stations, future towns, and etc.. Also, he (or his wife he says) definitely named CALDWELL, which is on the same line, directly situated between NAMPA and NOTUS. Also, Strahorn tended to operate pseudonomously — his favorite of his alter ego’s being the self-referential “Alter Ego”.... Western Newspapers called him “The Sphinx”.... And so on to today: His biography (90 Years of Boyhood, with its manuscript still in the archives at the College of Idaho) has never been published…. His wikipedia page, once longer than Hitler’s, keeps vanishing from the internet…. And Etc. And Etc….. Is all this sphinxiness enough, though, to explain why Starhorn might be explaining such a boring explanation almost 30 years later under the assumed identity of a “Mr. Blinkingdoffer”?...

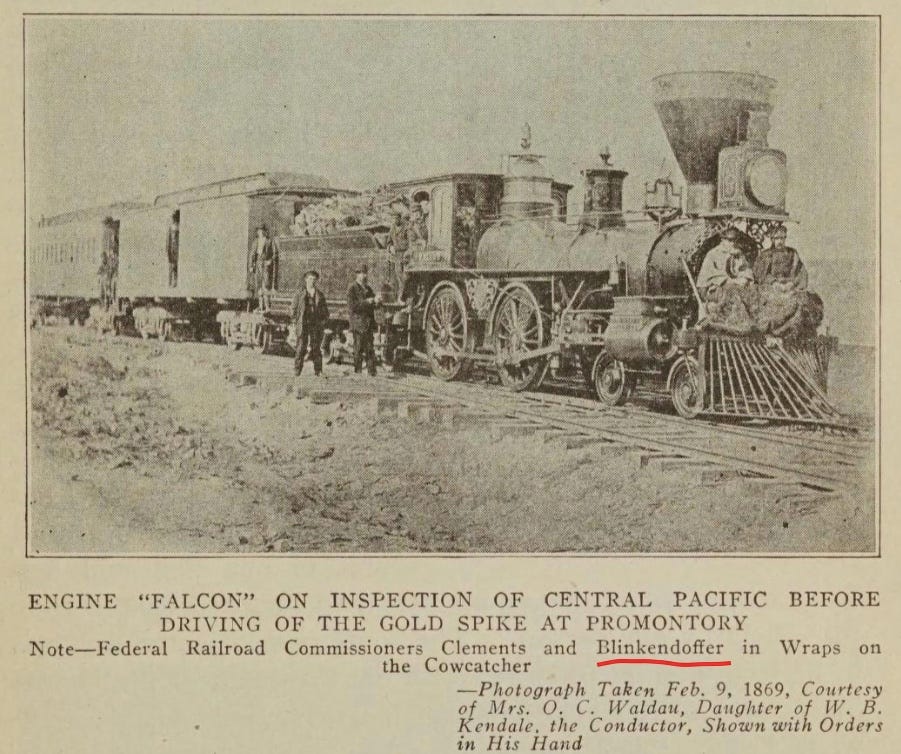

Another misspelling suggests otherwise. After googling BLINKENDOFFER, I find this 1869 photo + caption in Thompson’s Short History of the American Railways, 1925:

Not clear, though, which of the Federal RR Commissioners here is Blinkendoffer:

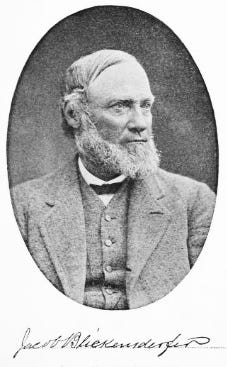

Here he is in a clearer picture:

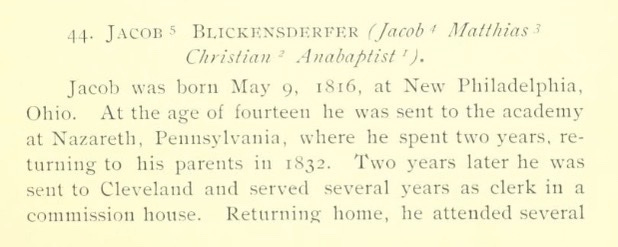

His name, it turns out, is Jacob BLICKENSDERFER. He was Chief Engineer for the Union Pacific RR, 1881-1886. His family, the Blickensderfers, were from Blickensdorf, a small hamlet in Switzerland. They were radical Anabaptists, expelled from the country by more reform-minded Protestants some time after the loss of the Peasant Wars.

In his History of the Blickensderfer Family in America (1899), Jacob tells about “the earliest authentic information of the Blickensderfer family in America”. He tells about how a document in the government archives in the city of Speyer, in Bavaria, tells about how, on 2/12/1716, an Ulrich Schneider received permission from the Electoral Palatinate Court to transfer ownership of his estate to a certain “Anabaptist PLEICKENSDOERFFER”.

“Anabaptist” was possibly not his real name. They possibly called him that in the paperwork because he was an Anabaptist, to emphazise his status as an Anabaptist. He had six sons, five of which emigrated to America. The names of the five sons were Christian, John, Jacob, Ulrich, and Jost.

In the Colonial records at Harrisburgh, Ulrich’s name appears as BLICKESTÖRFER. Jost is there too, as BLICKENSDÖRFFER, and later as BLICKENSTAFF. The descendents of Jost were all BLICKENSTAFF. The descendents of Ulrich were BLICKENSDERFER, FLICKENSTAFFER, FLICKENSTAFF, BLICK and FLICKER. Jacob BLICKENSDERFER does not mention how the other brothers spelled their names. Presumably something similar to BLICKENSDERFER.

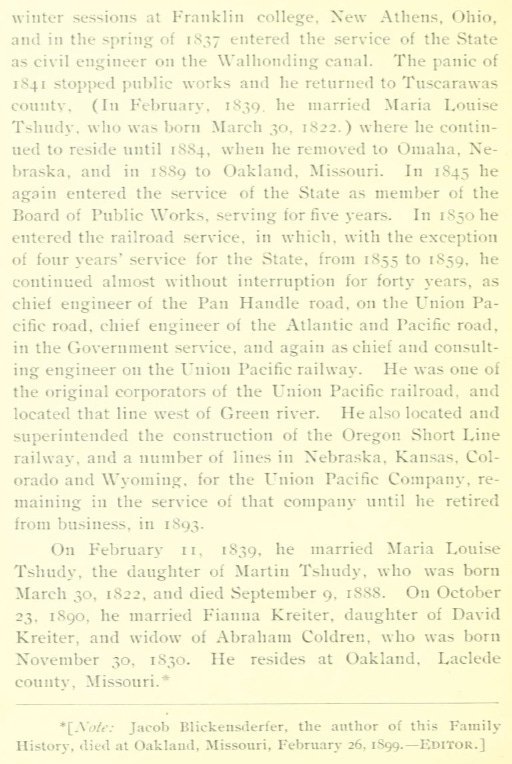

Jacob BLICKENSDERFER was descended from Christian. He was a precise and mathematical man — was briefly mentioned in Lukas’ Big Trouble (1997) as a “stolid Dutchman”. His History of the Blickensderfer Family in America, for example, is perfect. Here is the entry he wrote on himself:

That was written in 1988 — in Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. But going further back, to 1951, to Fritz Kramer’s “Idaho Town Names”, there is not yet the story about EP Vining and his Shoshoni dictionary. (...) Also note: “Green leaf, good to smoke” comes from Charles S. Walgamott, who is the one who, in the year 1927, gave us the obviously-false-but-nevertheless-memorialized idea that in 1859, near present-day Almo, there happened a Massacre of 300 Pioneers on the California Trail [see ALMO] (...) Also Note: In the years since 1988, Kuna’s Chamber of Commerce has made clear its preference for “end of the trail”. (...) Also Note: Kuna has been growing a lot lately… When I first wrote about this a few years ago, I speculated that Kuna has probably already crossed over into Phase 4. Then, some time after that, a friend told me about this article in the Idaho Press Tribune (12/18/2022) “fact-checking with members of Idaho’s Indigenous Tribes” about the original meaning of “Kuna” — mainly interviewing a Western Shoshone couple about how the name “Kuna” might’ve came from the Shoshone word “gu’na” (as it is currently spelled into the letters of the Ancient Romans), which is the Shoshone word for “wood”… I didn’t read it at the time — decided I didn’t want to be a ‘white guy with an opinion here’ anymore. But now, since I am returning to my opinion here, I look up the article: At bottom, the article makes an excellent argument for better education about Idaho's pre-“Idaho” History, and for some broader reactivation of Idaho’s less-USA-centered History……..((((Easy to agree with…. Off top of my head, for example: Insofar as we take the Pioneer Perspective on the Oregon Trail, we learn nothing about Idaho History. These OT Pioneer’s were just passing through, contributing no settlement or heritage or whatever to what we now know to be “Idaho”. The ones who stayed—the ones whose experience of the Oregon Trail is still reverberating in any relevant History here—are the ones the OT Pioneers called the “Snake Indians” (= mostly the Shoshone and the Bannock). In this way, insofar as it has anything to do with Idaho History, the Oregon Trail is Indigenous History. We teach it backwards when we teach the Pioneer Side.))))……….It’s just a little weird, though, how the article must center its argument around its news about the true meaning (the correct pronunciation even) of “Kuna”..………. Such is the Past, insofar it is “The News”………………… We see the same in Nampa in 1911… See Phase 4, and footnote number 2, where F.G. Cottingham does the same thing the IPT is here doing, but 1911-style….……………………… (...) To be clear though: However unlikely it may seem, it is not impossible that the Union Pacific RR Company may have, more or less accidentally, but still correctly somehow, re-applied a Shoshone toponym to one or some of the many places it was inventing across its depopulated SRP desert in the year 1883 ((Post “Snake War”... Post Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868… Post “Bannock War” of 1878…)) It was the power and the prerogative of the Union Pacific RR Company to be as considerate as it liked. This is just not news anymore. No surprise then that the Idaho Press Tribune does not mention the role of the Union Pacific in the invention of Kuna. Like: Says the News: “The Question is a question of Modern Historical Education about the News we just reported”. In this way, implies the News: ‘The Question is not, itself, a Historical Question….’ Obviously though, here at least, the Question is very-much a historical question: Is this some Union Pacific RR Company Official making up words or is this Boise Valley Native Tradition? (...) The question brings with it a special poison that could be only brewed in America. (...) For the essential book on the subject, see Philip Deloria’s Playing Indian (1998)……. (...) Deloria’s thesis, as I understand it, is this: By “playing Indian”---performing its own imaginary image of the “Indian”, instead of the Indian, in the place/land of the Indian, “White America” simultaneously displaces the Indian and creates its own White American Identity instead. (...) Note: It is a thesis that can be taken in a completely literal way: Playing “Indian” was exactly what those guys were doing when they dressed up like Indians and threw the tea in Boston Harbor. Playing “Indian” is exactly what I am doing when, reproducing the sounds of an imaginary “Indian Language”, I express my identity: “I’m Idahoan”. (...) Going back to the IPT article though — to be clear: None of this is to preclude any possibility of doing some better education about all the pre-“Idaho” History that is still living here in Idaho. It is just hard to see past the RR when you forget it’s there. (...).

Frege says, “Never ask for the meaning of a word in isolation, but only in the context of a proposition”. Wittgenstein explains why: “Only the proposition has sense; only in the context of a proposition has a name meaning”. This is the CONTEXT PRINCIPLE. We could imagine it applies here especially. Say: The “meaning” of the toponym (situated in some light historical/geographical context) is, at best, comparable to the “meaning” of the BAR in the incomplete picture: “A guy walks into a BAR…”... Also, the specific dubiousness of Cottingham’s method is not usually noted: “Is there a word in your language that sounds like X?” The problem is that, pretty much whatever is X, there is a word in every single language of the world that “sounds like X”.

Report on the opinion of the Nampa-Alberta Librarian comes from Skip Scanlan, Nampa-Idaho Librarian. See Skip’s notes, 8/27/2021: Mike sent us all pictures of the kids. They didn’t come inside today, but they were aggressively vaping in the square when I left. They do not think I’m cool……………………………..The New Consortium…………………………….…..Draw a line 701 miles due south, discover the barge “Nampa Public Library” in the Pacific, 1400 miles due south of the Alberta branch. There’s a google profile. There’s a phone number. You call it. They don’t know where the name Nampa comes from either.

Or nevermind…. RIP Nampa Water Tower — the Idaho one… Also, it is hard to make out in the photo, but the picture on the Nampa-Alberta Water Tower is showing three things: Wheat, Train, and The Water Tower.

Tempting, but not necessary — especially when it comes to the RR in the West: As with its Boise Bypass—where the RR crossed over 400 miles of unpopulated desert only to miss the only sizable town in the region by a few miles—there are official and unofficial interests at play. The Company’s official interests appear purely mathematical: how to construct the straightest possible line across the SRP…. The Company’s unofficial interests, meanwhile, are a lot more human and generic and technically complicated and basically obvious: They want to make as much money as possible for themselves and their affiliates. Like, obviously, this is why they bypass Boise (a town they don’t own), and decide to invent Caldwell (a town they will own) instead. Only in retrospect, has anybody in the Boise Valley ever taken seriously the Company’s official explanation. Only in retrospect does the official explanation (a thin mathematization of the obvious explanation) start to look like a different explanation. (...) So basically the same for RR’s Indian Names here: Their Specific Answer gives their Official Explanation = a thin mathematization of their Unofficial Explanation and/or Generic Answer (...) Interesting to note, though, the relative complexity of the Unofficial Explanation here: It is not necessarily the case that the RR Company would’ve been fully conscious of its own Unofficial Explanation.